Covid has created a shift-change towards managing conditions at home. Big pharma and investors are hopping on this big time. SmartHealth’s Pádraig Belton looks internationally at medtech challenges in cardiovascular health, what works in the real world and who’s going to pay for it

Laurence Pearce, founder of Lifelight, had a personal reason for beginning his startup, which uses a smartphone camera to measure your blood pressure.

“About 15 years ago my mother died of an aneurysm,” he explains.

She had a previous aneurysm before that, and had been given a BT plastic pendant alarm to wear, to notify emergency services if she required help.

“It’s just so ugly, it’s unfashionable,” he says, as though device makers thought “let’s just give all the octogenarians some ugly thing to wear around their neck, like cattle.”

As a result, his mother hadn’t been wearing the pendant. His mother’s experience left Pearce interested in developing “a more humane” way of monitoring people’s health, “something they fully consent to, that they’re fully involved with.”

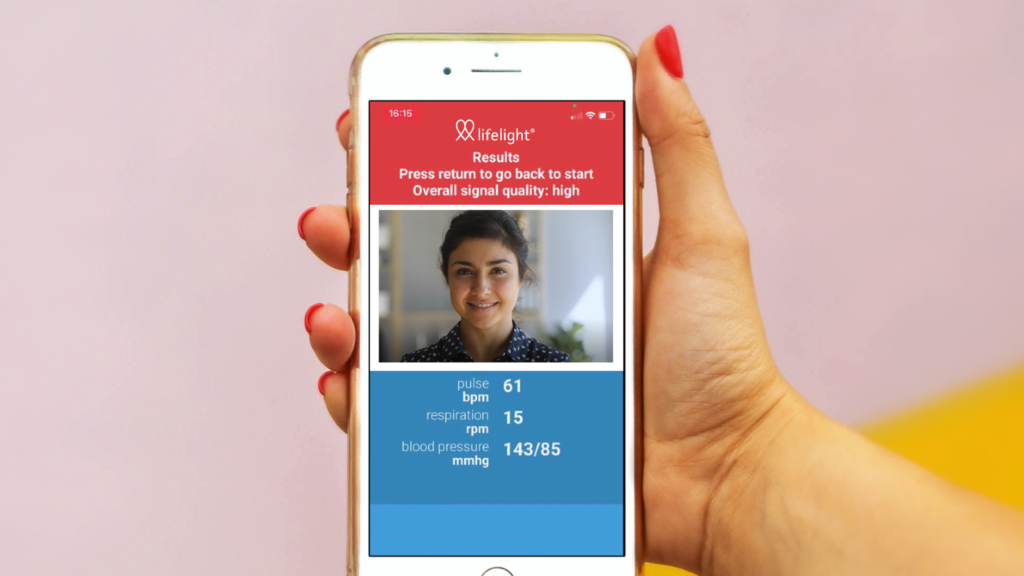

Then, in 2014, at MIT he saw a demonstration of the science allowing researchers to measure someone’s blood pressure from “tiny changes in the skin colour of their face, with every heartbeat,” he says.

Not just skin deep

The science is called remote PPG. PPG is short for photoplethysmography, which means using optical tools to measure changes in blood volume within someone’s vessels, instead of using a blood pressure cuff.

One per cent of your skin colour changes with every heartbeat. An ordinary smartphone camera, capable of capturing 30 frames per second (fps) video, can then produce a waveform of how these changes happen.

And finally, machine learning algorithms can learn how to translate these waveforms into information about a person’s blood pressure.

This is useful because, without owning your own blood pressure cuff or going to a GP surgery, you can measure your own blood pressure to see if it is high.

This means you can know if you run an elevated risk of heart disease, and could benefit from a doctor’s advice and maybe blood pressure medicine.

It also means doctors who practise telemedicine – seeing patients remotely over a video conferencing app – can have reliable enough information about a patient’s vital signs, to use in prescribing or changing prescriptions.

This is all especially helpful after the coronavirus pandemic has led to a rise in managing health conditions like cardiovascular health at home. As well as since there’s a ticking time bomb in treating conditions like hypertension, with many people skipping health check-ups since 2020.

Last of all, looking at a smartphone screen “doesn’t establish the same white coat syndrome as going to a GP surgery,” says Josh Sephton, Lifelight’s chief technical officer.

It’s a “well established fact” that putting on a blood pressure cuff in a doctor’s office makes your blood pressure go up, he says. But we’re all reasonably accustomed by now to looking at our mobile phone screens for 40 seconds.

Seeking the sick

In 2016, a “relatively small grant” let Pearce’s start-up build a first prototype. The team were extremely excited to show it to clinicians. But the first time they showed it to a doctor, they were asked “it’s game changing, but does it work with sick people?”

Since they had trained and tested the prototype on “young healthy tech guys” they answered “we don’t know, it’s never seen a sick person, so it probably doesn’t work on them.”

So the next step then involved a partnership with Portsmouth Hospitals NHS Trust, where a £1million grant allowed the Lifelight team to make two recordings each of 8,500 patients in the hospital, while measuring their blood pressures.

There have been four studies since, to further train the algorithm – where the researchers have tried to make it work better on under represented groups in their training set up until then.

These included the very sickest patients, as well as on the skin of people of colour. And a current study has been an end-of-life study with Trinity College Dublin, where the start-up is working together with oncologists to find ways to monitor the blood pressure of cancer patients in hospice care “in a comfortable, non-invasive way”.

A lesson in leavin’

So what are the challenges and lessons that Pearce and his colleagues have to offer to other start-ups, with interesting ideas about medtech devices to help in managing other conditions at home? One has to do with building a product first in local markets like the UK and Ireland.

The US healthcare market “is massive but also complicated, and one of the most difficult markets to enter a new product into globally,” he says.

In the case of Lifelight, an early supportive relationship with NHS trusts helped the startup get going, with first customers in the Isle of

Wight and Hampshire trust and a kiosk in a shopping centre in Basingstoke.

Another, related lesson was interoperability – having an API that “talks the right languages in health care” and connects with how electronic patient records are stored in different health systems. And a final lesson is building partnerships offering a start-up’s technology to other providers and platforms.

Lifelight, for instance, is offering its video blood-pressure tech to telemedicine platforms. “You can take that tech, and put it directly in the call when you’re talking to the doctor. To make this global, we don’t have scale to do

that,” he says.

“Our approach is to look for platforms already being built, digital health platforms that have a wide reach. All this stuff grew rapidly during the pandemic. We partner up with organisations around the world.”